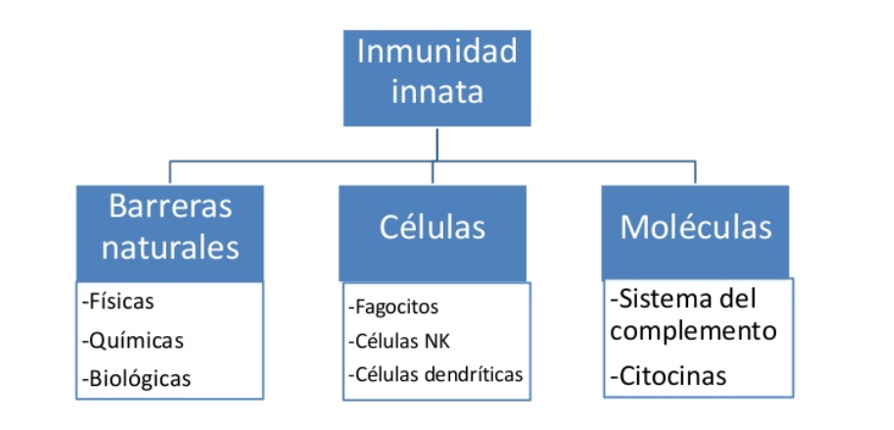

In general, when we think of innate immunity, we imagine impenetrable prison-like barriers; although in this case, not to prevent things from escaping or leaving, but to keep things from entering. Under this premise, we all know that innate immunity consists of a series of different types of barrier that prevent pathogens, or other agents, from entering the organism. It would therefore be the first line of defence against these invasions.

But while it is true that, in general, this immunity is quite effective in preventing the entry of a large number of undesirable actors every day, there are a number of actors who have specialised in circumventing and breaking through these barriers. And if that happens, other parts or mechanisms of the immune system come into action to try to neutralise them.

What is going wrong in the humoral immune response to PRRS disease

When pigs are first infected with PRRS, an innate immune response occurs, inducing interferon production by dendritic cells and other mechanisms, followed by activation of the acquired immune response and antibody production.

It has been more than proven that, in general, the pig's immune response against the PRRS virus is not entirely efficient, resulting in persistent infections, long viraemia, constant recirculation of the virus, secondary infections, lack of protection against heterologous reinfections, and a series of other consequences due to this failure in the defence, fight and elimination of the enemy.

One of the mechanisms of the PRRS virus in pigs is evading the protective army and carrying out its invasion; more specifically, it neutralises said battalion using various mechanisms to prevent it from acting in an adequate and/or coordinated manner, and is able to modulate, interfere and/or inhibit a series of processes necessary to constitute immunity, both innate and adaptive. It does this by infecting cells of the innate immune system and causing what is called immune system dysregulation. All of which can increase the replication period of the virus, thereby significantly enhancing the possibility of transmission.

In the event of infection with the virus responsible for PRRS, inhibition of the expression of some TLRs (toll-like receptors) in macrophages and dendritic cells may occur. TLRs are receptors capable of recognising elements on the surface of bacteria or viruses, cell-derived molecules that have been altered, and nucleic acids from viruses when they have infected cells. All of this is capable of initiating the immune response, which can range from inflammation to the establishment of an adaptive-type response; it can activate the secretion of cytokines that increase the resistance of infected cells, the secretion of chemokines to recruit a greater number of immune cells, and initiate apoptosis to reduce the spread of the virus.

But this virus is capable of much more, such as not inducing interferon-α production, or blocking the innate interferon response, and modulating the production of certain cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF-alpha. Or, conversely, specifically inducing cytokines that function to regulate or inhibit the immune response, such as IL-10. This PRRS virus can also lead to inhibition of Natural Killer cell activation or preventing the antigen presentation from occurring properly.

In other words, we are dealing with an agent—this word has never been so appropriate—that is able to modulate the immune response of the host, so that it can unleash all its activity: replication, distribution and latency in infected pigs. What a thing for pigs and us to have to deal with!