Worker bees live for around six (6) weeks during the active season, and for up to three (3) months if hatched in the winter. That is, assuming they have eaten a balanced diet (varied pollens), have not had any diseases or parasites, and have been reared and live in a toxic-free environment. Any one of these factors, if relevant, may destroy the life expectancy of the bees. Or, even if they are less relevant, their joint action can cause the same damage, as there is a synergy between them.

Varroa

Varroa feeds on bee fats, and that depletes their body reserves, prevents the formation of certain hormones, reduces the production of royal jelly, etc. And these disruptions negatively impact the smooth running of the colony.

This situation is especially critical in the late summer brood decline, when varroa is concentrated on fewer pupae, and causes more damage. Any such damage will take its toll, as it is autumn-born bees that must maintain the colony over winter, and uproot it in early spring. Accordingly, if they are not long-lived, and/or have no body reserves, the hive will have problems. Here we should remember, as mentioned in the post "Varroa, critical moments of action", that: 3% varroa on bees, or its equivalent on brood, means 30% winter mortality.

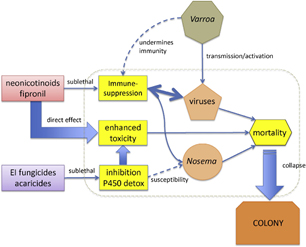

In addition, varroa spreads viruses and other diseases, decreasing the vigour of the bees and the colony. In particular, the Damaged Wing Virus (DWV), which multiplies inside varroa without causing any apparent damage, transforms each of its stings on a bee, or pupa, into an injection of millions of virus particles.

Therefore, it is essential to know how much varroa we have in the hives at the end of the summer, so that we can plan the relevant actions, as explained in the post "Varroa, he who does not measure does not improve".

Starvation

In our Mediterranean climate, after the end-of-summer brood drop, hives have a growth phase, thanks to the blooms caused by the autumn rains. If there are any. With these blooms, the colony gains young bee population, young bees build up body reserves in their abdomen, and reserves are also built up in the hive for overwintering.

But recently there have been changes in seasonal and rainfall patterns, which sometimes result in the loss of these late blooms. This means that the colony reaches winter with older bees (which will not last until early spring) and with fewer body reserves, and fewer combs with honey and especially pollen reserves in the hive.

Bees' body reserves can be assessed by the length of their abdomen. Their "love handles" are under the third dorsal half-ring of the abdomen (Photo 1), so "fat" bees will have a longer abdomen than wings; conversely, "skinny" bees will have a shorter abdomen than wings (Photo 2).

There will also be bees "cut off" by varroa attack (which consumes the fat), or nosema (which destroys the gut).

Before any non-flowering season, such as winter, the level of reserves in the hive combs, honey andpollen, which should be varied, at least of various colours, should also be assessed.

Poisons

The vast majority of our hives do not suffer from external poisoning, as they are usually kept in natural vegetation.

But they are all treated with acaricides against varroa, the residues of which accumulate in the wax. And they pass from this to the ensiled pollen in the cells, generating sub-lethal toxicities, which do not kill, but do cause harm. These residues have been known to affect bees by "switching off" detoxification genes, lowering their immune system, making them more prone to disease (Figure 1), and decreasing their level of foraging activity.

Drones are affected by decreasing their percentage of active spermatozoa, leading to more queen replacements, which "drone" earlier.

Special attention should therefore be paid to reducing the waste from varroa treatments. We must maintain the treatments for the appropriate time, and withdraw them if necessary.

It is also necessary to remove treatment residues (strips, etc.) from the combs before melting them to avoid an "infusion" of acaricides in the liquid wax at the waxworks when everything is melted together. The waste must be destroyed through the regulatory circuit, in accordance with current legislation on waste collection and destruction.

As a guideline, there is four (4) times less residue in the wax from the operculum of the supernatant than in the wax from the brood chamber.

A large part of the high winter mortalities are avoidable by monitoring these three (3) critical points.